Live Smart | home

Customer Service

Disclosure & Policy

1(888)875-3582

orders, questions, fax

9:00am - 5:00pm CST

|

Email Invoicing with Paypal,

No Paypal account required

credit card by phone

|

What is Popular?

Herbal Adjustment Joint Pain

BPW and BCW

Blood and Organ Cleansing

CCE-W Bowel cleanse

|

|

High Quality

Thyroid Balancing

Bulk and

single jars

|

Supplements

Spiritual

Health

Pet Corner

Living Green

|

Tea Master

learn how

Pure Herbs

|

Organ

Cleansing

|

Cold Remedies

Articles

and more

|

Herbal Remedies

Instruction

Articles

|

Young Living

Ancient Biblical Oils

|

Store

Front

|

|

© www.blueirissanctuary.com 888-875-3582 Nutritional Consulting ~ Master Herbalist available

© www.blueirissanctuary.com 888-875-3582 Nutritional Consulting ~ Master Herbalist available Right Brain Left Brain How these influence our abilities in sports and life

Spring 1998 - "Train Your Brain to Ski with Symmetry" by Deb Ackerman Willits

This article is reprinted from The Professional Skier. All copyrights apply. Please see ourdisclaimer notice page.

It's early morning, the sun is out, and there's 14 inches of fresh powder on the ground. I stand poised at the top of the Spiral Stairs bump run.

The slope looks really steep, and there's lots of snow between the moguls. My heart rate is up.

I push off and instinctively make my first turn a left one. The snow is light and deep, and my turn is effortless. But as I make a few more turns,

each feels more difficult than the last. Then I notice that I am dragging my right hand and locking my downhill leg on my right turn. My inner

voice kicks in, spoiling the moment: "Get your hips downhill, stop dragging your hand, and relax your downhill leg." I stop to regroup and decide

to seek out an easier run.

Does this scenario sound familiar? At one time or another you've probably noticed a difference between right- and left-sided movements in your

skiing, as well as that of your students. This is normal: almost everyone favors one side. This article will attempt to explain why and will describe

two simple dryland exercises that should help you make more symmetrical movements.

The Stress Factor

Although some people consistently demonstrate stronger motor skill movements on one side of the body, others appear to perform right-body and

leftbody movements equally well. Stressful situations, however, often pull these individuals out of their comfort zones and elicit asymmetrical

performances. The stimulus could be intimidating terrain, the gates on a race course, deep powder, or the presence of a video camera. It could even

be a really cold day or a friend's challenge to "Follow me!"

Because learning a new skill is often an inherently awkward situation for most people, a novice skier is immediately out of his or her comfort zone

and will exhibit a "weak side" right away. For an expert skier, whose comfort zone is much larger, this asymmetrical trait may not appear until the

skier drops into a double black diamond bump run.

As instructors, we all have tricks for trying to help ourselves and our students. "Stop on your weak side." "Always start with your weak turn."

"Look from track to track as you shift your weight." "Feel what your good side is doing and try to make your other side do the same thing." To some

degree, this advice can help. But when we make these directions our mantra, we often find ourselves thinking too hard, forgetting to enjoy the ski

experience. In much the same way that medicine for the common cold eases the symptoms without curing the virus, it seems as if we concentrate on

addressing the symptoms of asymmetrical skiing rather than solving the problem. In addition, if we explain to students the reasons behind why we

do something--rather than just tell them bow we do it--we can help make lessons a more fulfilling experience.

The Reasons Behind Asymmetry

In my quest to learn why human motor skills tend to be asymmetrical, I talked to ski instructors, schoolteachers, chiropractors, physical therapists,

and kinesiologists. Their explanations varied, but many of them felt that skier misalignment was part of the problem.

The ski industry has been exploring the alignment arena for years, experimenting with footbeds, wedges, and canting adjustments. Footbed and

alignment specialists have even opened businesses at many resorts to help skiers make that jump to the next level. Granted, minor adjustments

often make big differences in our skiing and may enlarge our comfort zone, but there's still a ceiling to that zone. And at some point that weak side

will rear its ugly head. There had to be more to asymmetrical skiing than alignment alone.

My search led me to something far I more complex than I bargained for. It led me to the brain.

This Is Your Brain

Before you can understand why many of us favor one side of our body, it helps to understand the complexity of the brain's structure and how it

functions. The brain comprises two identical hemispheres. The detail-oriented left hemisphere is generally referred to as the "analytic brain,"

and the more global right hemisphere is known as the intuitive or "Gestalt brain" (table 1 below).

Table 1: Hemispheric Differences

|

||

Logic (Left)

|

Gestalt (Right)

|

|

Sees the pieces first

|

Sees whole picture first

|

|

Parts of language

|

Language comprehension

|

|

Syntax, semantics

|

Image, emotion, meaning

|

|

Letters, sentences

|

Rhythm, flow, dialect

|

|

Numbers

|

Image, intuition

|

|

Analysis - linear

|

Intuition - estimates

|

|

Looks at differences

|

Looks at similarities

|

|

Controls feelings

|

Free with feelings

|

|

Planned, structured

|

Spontaneous, fluid

|

|

Sequential thinking

|

Simultaneous thinking

|

|

Language-oriented

|

Feelings, experience-oriented

|

|

Future-oriented

|

Now-oriented

|

|

Technique

|

Flow and movement

|

|

Sports (eye, hand, foot placement)

|

Sports (flow and rhythm)

|

|

Art (media, tool use, how to)

|

Art (image, emotion, flow)

|

|

Music (notes, beat, tempo)

|

Music (passion, rhythm, image)

|

|

Certain parts of each hemisphere operate the same functions, such as sensory and visual perception, as well as motor control for the opposite

side of the body. However, each hemisphere has unique functions that are not necessarily represented in the other hemisphere. For example,

the ability to understand and process language is located in an individual's dominant hemisphere. Healthy individuals use both hemispheres but

favor one, especially during times of stress. Experts disagree, however, over whether we are born with this preference or develop it at a very early age.

Communication between the brain's two hemispheres occurs through a large bundle of nerve fibers (neurons) called the corpus callosum. These

neurons join the left and right hemispheres and act like a bridge, transporting information from one hemisphere to the other. During stress, the

hemispheres stop communicating with each other, and the hemisphere that controls our "favored side" takes over, resulting in more pronounced

differences in motor function, sensory perception, and visual understanding than during nonstressful moments.

In addition, we also favor one eye, ear, hand, and foot over the other. These preferences-coupled with the fact that each hemisphere of the brain controls

the muscle functions on the opposite side of the body--can generate a number of combinations. Therefore, everyone has a highly individualized set of

preferences for learning, processing information, and moving. And we can make no generalization relating brain-side preference to turn preference.

Basically, the key to skiing more symmetrically is to maximize the output from your whole brain.

This Is Your Brain On Skis

Both left and right turns seem effortless when we ski a freshly groomed blue run, because both hemispheres of the brain are communicating and

dictating movement. This is known as being in "the zone" (see "Getting Zoned," fall 1997). But if we run into an unexpected patch of ice, our brain

output may become asymmetrical. As a result, our motor function and skiing ability may also become asymmetrical.

When learning a new activity, we generally improve with practice. As we practice, nerve impulses travel from the brain through the spinal cord to the

peripheral nerves, where they activate muscles. Sensory information is then sent back to the brain via the same route. There is some controversy

surrounding why we improve with practice, i.e., whether learning takes place at the brain, spinal cord, muscle, or nerve level but no one seems to

deny the overall benefits of practice.

Improving Brain Performance

One key to improving performance is to facilitate the transfer of information around the nervous system. This includes improving communication

between the hemispheres through the corpus callosum. In times of stress, the transfer of information breaks down. Although not yet scientifically

proven, it would make sense that improving the connection between hemispheres would improve performance. With improved communication,

think what we could do.

While conducting research on dyslexic individuals, Paul Dennison, Ph.D., developed some simple and specific exercises to integrate the two

hemispheres into a functioning whole. These are outlined in Brain Gym, the book he developed with his wife, Gail. Dennison pioneered a field called

educational kinesiology, which combines techniques and information from language and motor development, acupressure, yoga, developmental

optometry, and brain research.

Another book, Smart Moves: Why Learning Is Not All in Your Head, provides convincing evidence that supports the efficacy of Dennison's exercises.

For example, Smart Moves author Carla Hannaford recounts a 1991 invitation to work with Botswana Insurance Company trainees to improve their

rate of success in taking the annual insurance exam. (The failure rate generally averaged more than 70 percent.) Hannaford met with the group in

February and suggested the candidates use Brain Gym exercises while they studied for the May exam. Three months later, every candidate passed

the exam, and one man who spent the first half-hour of the timed test doing the Brain Gym exercises became the first South African to achieve a

perfect score.

Brain Gym exercises are designed with specific outcomes in mind; some are better for strengthening mental capacity while others are intended to

elicit whole-brain performances during sports and other physical activities. Patti Templin, an educational kinesiologist in Telluride, Colorado, uses the

following left- and right-brain integration exercises in training sessions with the Telluride Ski School. Annie Vareille Savath, ski school director at

elluride, starts her day with these exercises and often uses them with her students as well. Savath says the exercises help her to get centered and

avoid overanalyzing everything. In addition, she uses them to bring her performance back together when she's tired.

Brain Gym Exercises

You can incorporate the two exercises that follow into your existing workout program,

or you can perform them in the morning when you get up.

Both exercises can be done while you are standing or lying on your back.

Performing them on your feet, however, offers the added benefit of promoting

better balance.

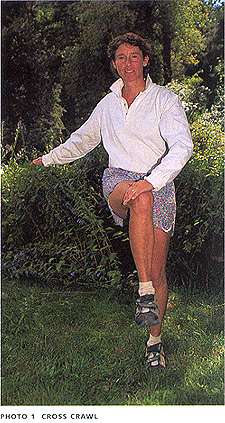

Cross Crawl

|

Crawling--simultaneously moving one's arms and legs--equally stimulates both sides of the brain and eases the learning process (Hannaford 1995). It follows, then, that the Cross Crawl would be an excellent exercise for activating full mind-body function before physical activities such as dancing and various sports, including skiing.

By touching the right elbow to the left knee and then the left elbow to the right knee, you can activate large areas of both brain hemispheres. When you do the Cross Crawl on a regular basis, you stimulate more nerve networks, potentially improving communication between the two hemispheres.

To help your students achieve whole-brain skiing, have them repeat the Cross Crawl 7 to 10 times on each side both at the beginning of the lesson and at the top of a challenging run.

|

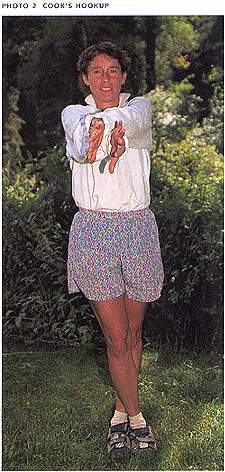

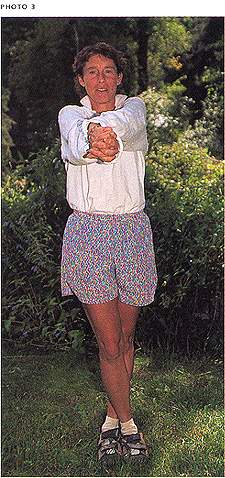

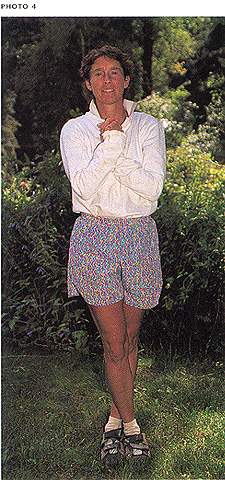

Cook's Hookup

The complex crossover action used in Cook's Hookup affects the brain in much the same way as the Cross Crawl. This exercise can be performed

while standing, sitting, or lying down. Hookups are especially helpful if you do them right after you wake up in the morning and whenever you face a

stressful situation.

First cross one ankle over the other. Then stretch your arms out in front of you, with the backs of your hands together and your thumbs pointing down.

Lift one hand over the other (with your palms facing each other) and interlock your fingers. Roll your locked hands straight down and in toward your

body so they eventually rest on your chest with elbows pointed down. Hold the position for two minutes to maximize the benefits.

Don't let the simplicity of these exercises make you think that they're ineffective. Give them a try and see if they make a difference for you and your

students. By stimulating both hemispheres of your brain and taking a more balanced view of life, you can open yourself to new possibilities. In addition,

having a basic understanding of how your brain works and practicing whole-brain exercises can help you improve your overall capabilities, reduce your

chances of injury, and take some of the anxiety out of previously daunting situations.

Deb Ackerman Willits is the director of the Telluride Nordic Center in Colorado and a second-term member of the PSIA Nordic Team. She is also a

certified Level II alpine instructor at the Telluride Ski School, an examiner in track and nordic downhill, and the PSIA Nordic Education Committee

chairperson.

References

Hannaford, Carla. 1995. Smart Moves: Why Learning Is Not All in Your Head. Arlington, Va.: Great Ocean Publishers.

Dennison, Paul, and Gail Dennison. Brain Gym. 1989. Ventura, Calif.: Educational Kinesthetics.

Templin, Patti Educational Kineasologist, Teluride, Colorado

The Heart Wall ~ Emotions | Power Words - How they can change your life | DNA and the Mind/Body Connection -Scientifice Proof | Use Dream Time to Solve Promblems | Mind and Prosperity | Is Opportunity Knocking? How to Hear the Signal | Exercise Power over events in your life | Meditation how to's by Joel Goldsmith | How to achieve what you want work sheet | Polarity Thinking and How it helps to overcome Mental blocks | Procrastination and how to overcome | Right Brain Left Brain How these influence our abilities in sports and life | Motivation and Talent | A great interview on the lessons of life

Blue Iris Sanctuary

Copyright 2013 All Rights reserved.

No copying, selling or using any of the material on this site without permission

© 2013 Blue Iris Sanctuary All rights reserved.

This Web site contains copyrighted material, trademarks, and other proprietary information.

You may not modify, publish, transmit, participate in the transfer or sale of, create derivative works of,

on in any way exploit, in whole or in part, any material is strictly prohibited.

None of what is recommend in this site is to be in leu of proper medical help. We do not treat disease in any way.

We are here to educate you and give you information on the alternative processes available to you so that you

can make informed decisions and take charge of your own health issues. We do not accept any liability for the

advise and products we offer. We are required to advise you that none of the information or products offered

on this site is accepted by the AMA nor the FDA. Please be advised and always seek professional medical

advise when undertaking any suggestions in this site. Disclaimers and Policy